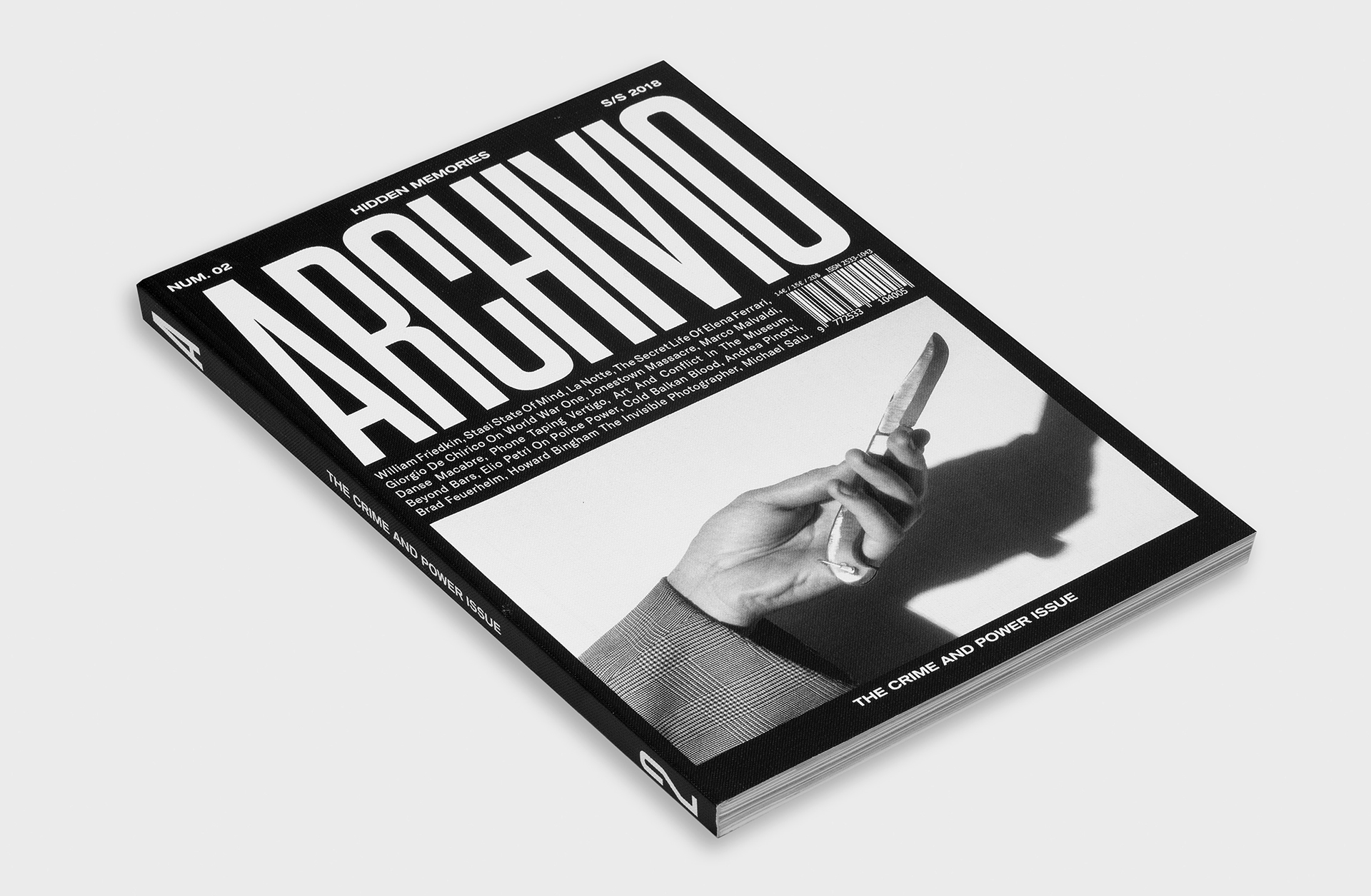

Archivio Issue 2

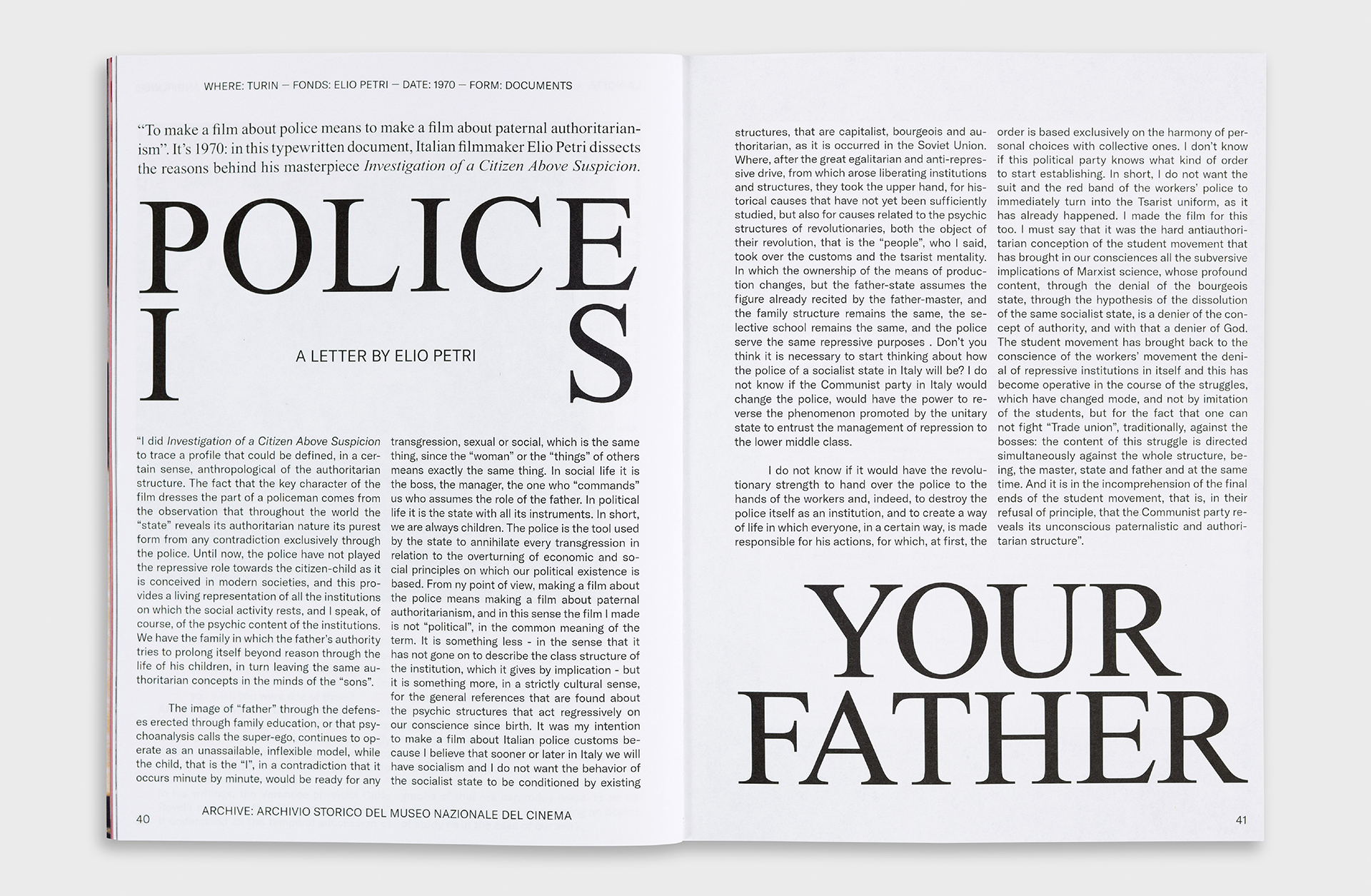

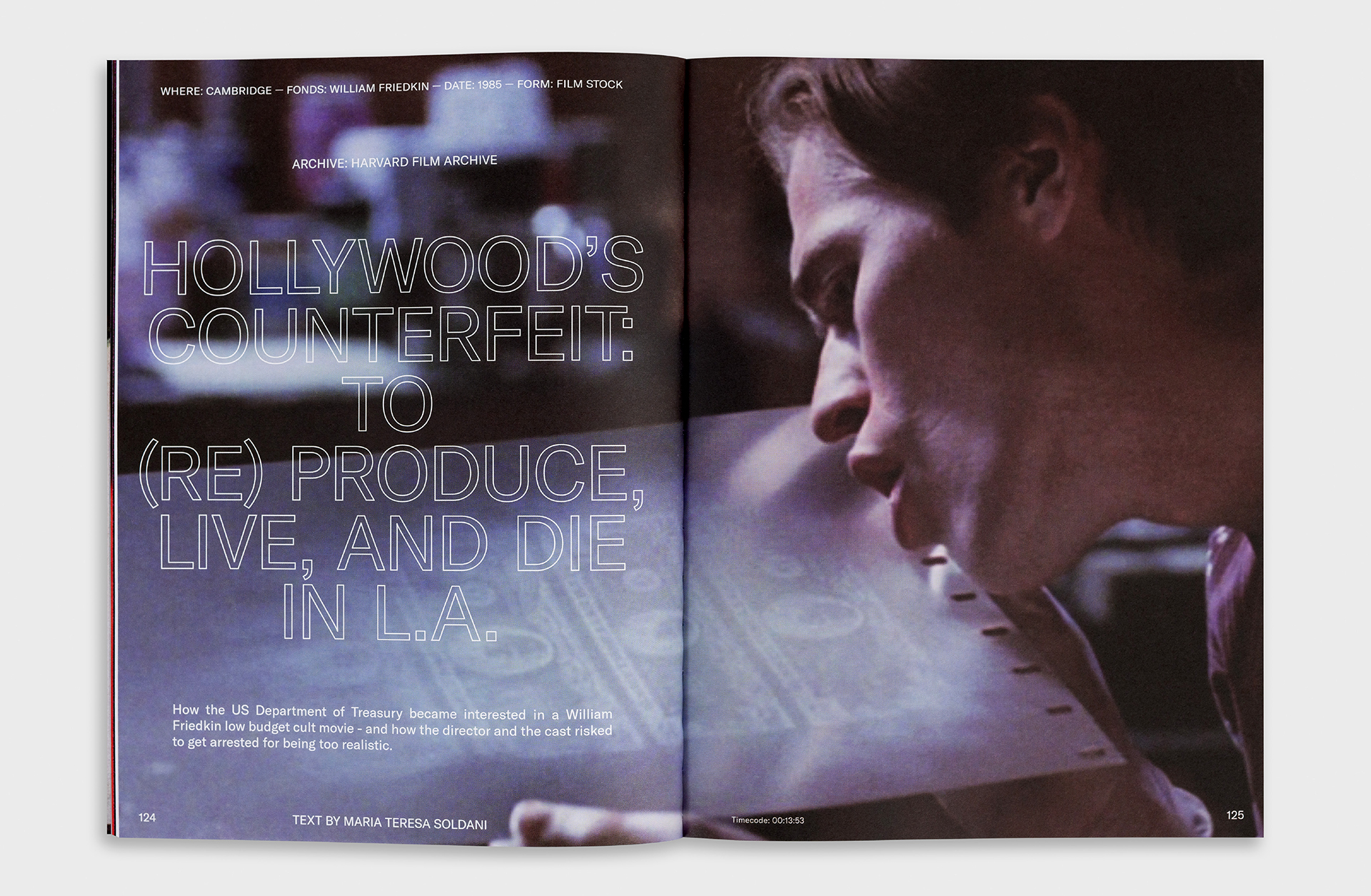

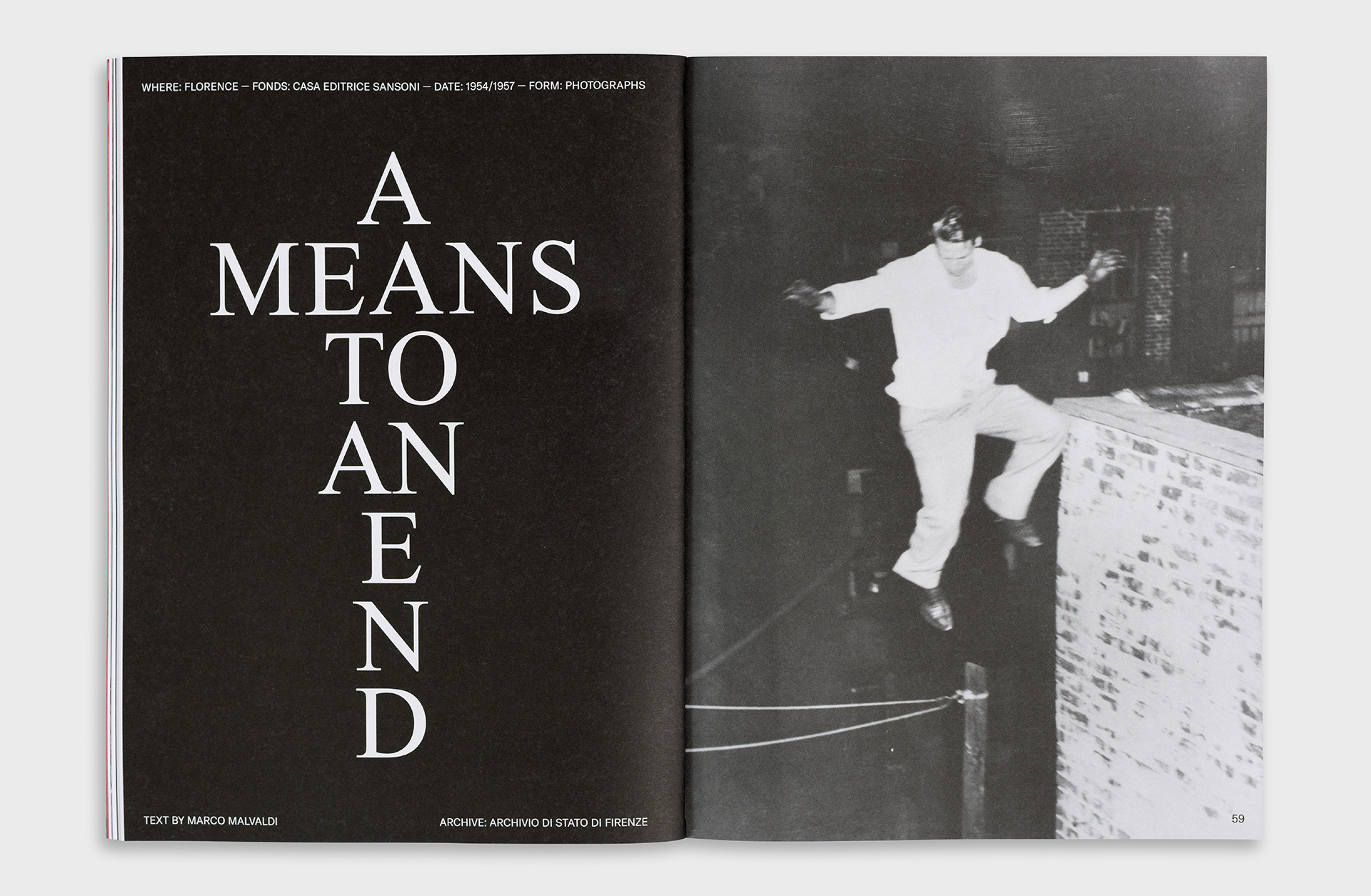

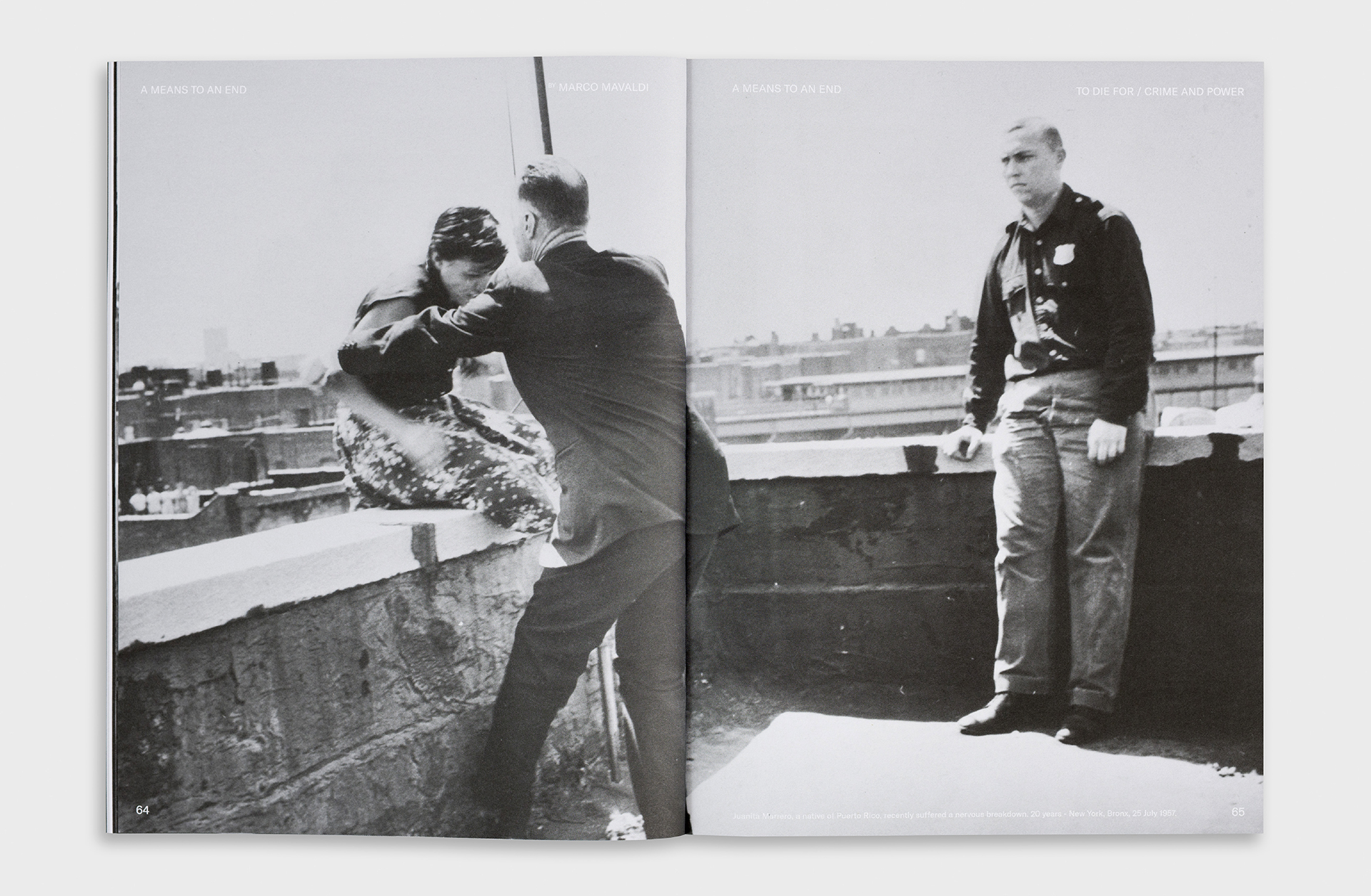

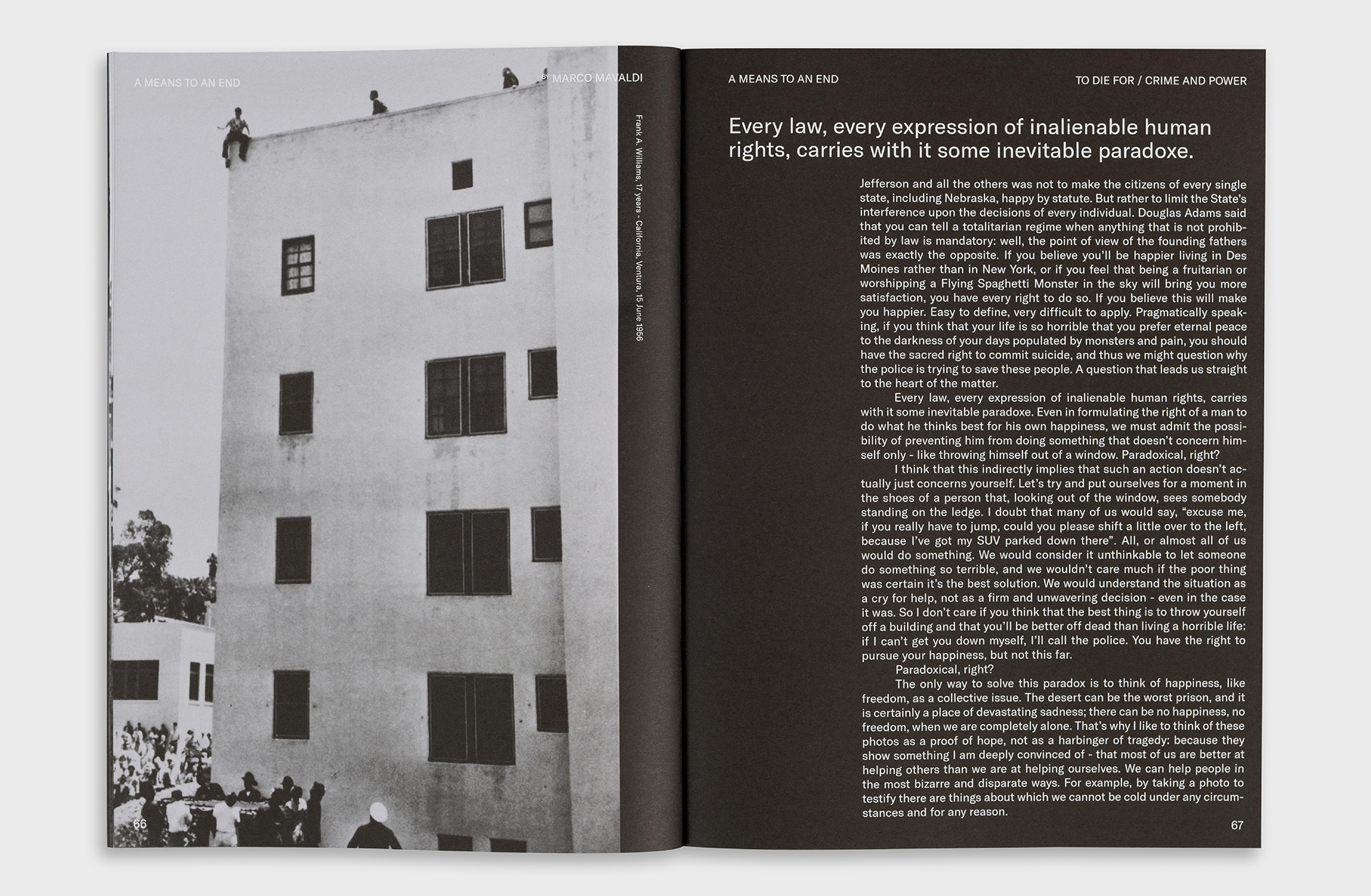

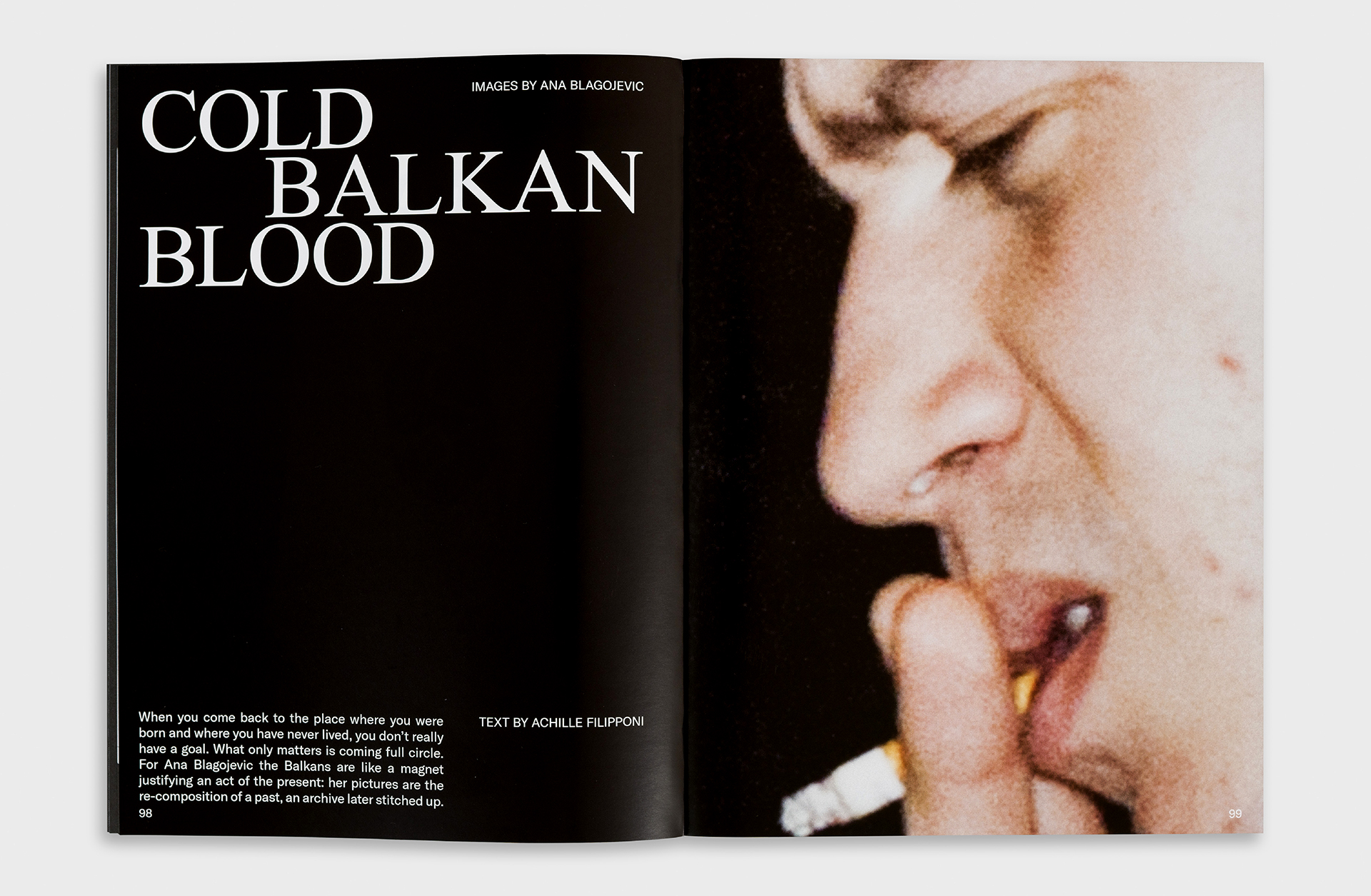

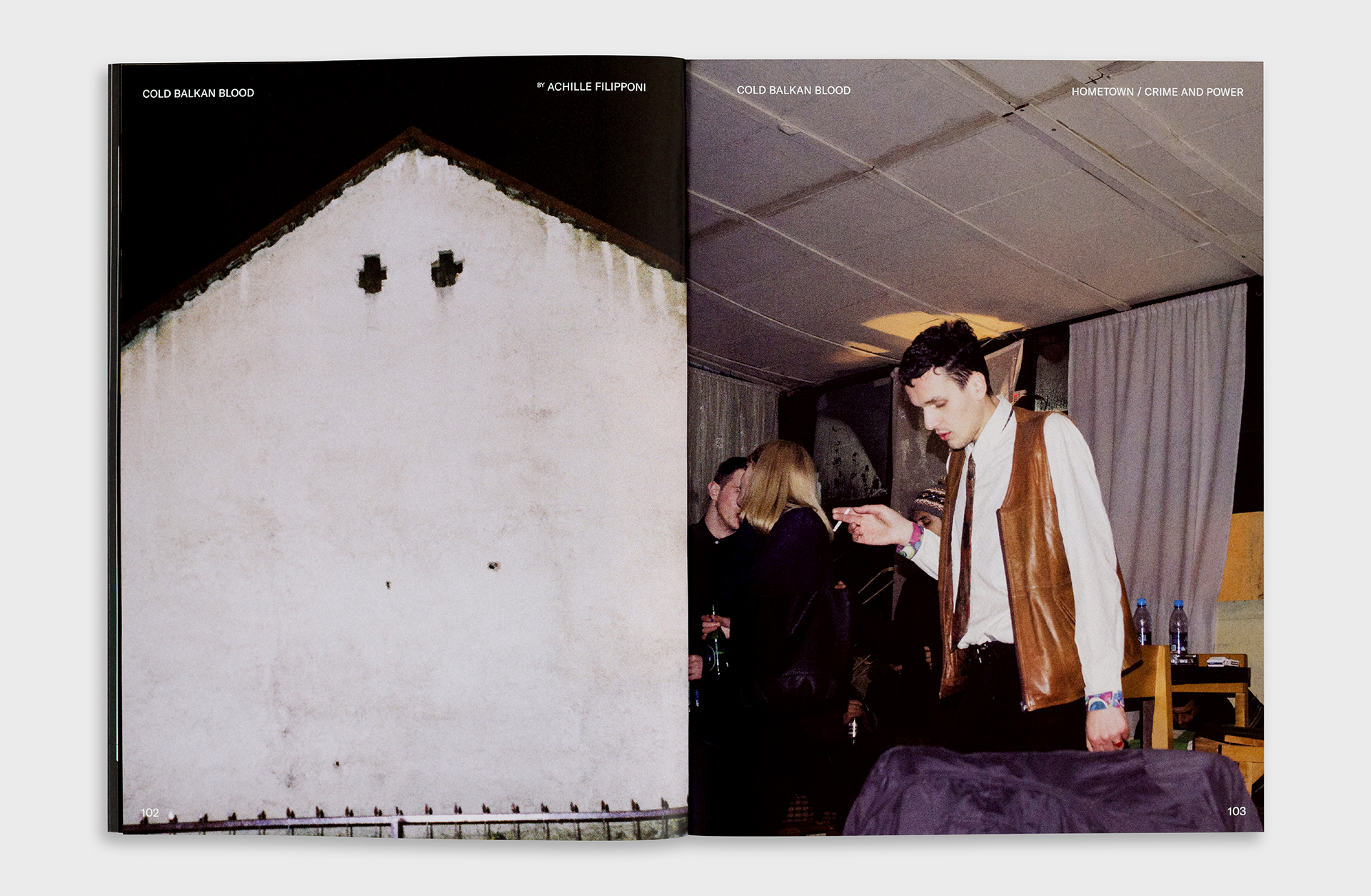

The idea for this issue sprang from a reply letter written by Elio Petri to a journalist in 1970, which was found during research in the Museo Nazionale del Cinema historical archive. In the letter, the great director reflects on the anthropological profile of the authoritarian structure, taking into consideration the function of the police and the state and relating them to the father figure. Children are subject to their father’s authority and they cannot rebel against it. Instead, they identify with him, and, as they grow up, they remain in the same position of subjugation to a master, who uses the police to prevent them from transgressing. While in the family authority is expressed by the father figure, according to Petri, the state reveals its authoritarian nature through the police. Nevertheless, their shared mission is to prevent transgression. So, for Petri, making a film about the police meant making a work on paternal authoritarianism, the mental structures that act regressively on our consciousness right from birth, and not the actual power structure. The first film in the Trilogia della Nevrosi (Neurosis Triology) indeed deals with the relations between father, power and state, through a prevalently psychological mental disorder, deriving from the unconscious conflict between the individual and the surrounding environment. This second issue is a collection of inquests, experimental literature, cold cases, crime stories and dark cinema, where violence reverberates upon the story in the form of the victims’ and killers’ memories. In the volume we find the mystery of Elena Ferrari, pseudonym of Olga Revzina, spy and poet who recruited engineers in the West in the 1920s; analysis of works such as ‘La danza macabra europea’, made by Alberto Martini between 1914 and 1916, in which the author evoked the war crimes inflicted by power; and photos and articles taken from La notte, cult Italian daily from the 1970s that dealt with crime news using an exceptionally high-profile photographic language. The final collection gathers together fragments of unresolved mysteries in which power is a crime and crime is power. The archives thus show just how thin the boundary between right and wrong is and invite us to ask ourselves what is more frightening in today’s society, the lack of information or the enormous power to decide what will remain. So, archives are not just a real, living source, but also a strongroom that stores and stages information and data in a dialogue which depicts the event in what can at times be a totally arbitrary manner. The reflection by Giacomo Papi in the short essay ‘You Are Not Alone’ is also interesting, as it connects the Internet phenomenon with the brilliant work of Simon Manner in the Stasi archive in Berlin. In the novel 1984, George Orwell wrote: ‘Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past’, pointing to a dystopia in which power controlled the past, present and future. These words echo through the incredibly rare documents in this issue: private photos of a soldier in Iraq during the First Gulf War accompanied by the literary experiment of Michael Salu; suicides captured by photo reporters in 1950s America; and the last photos taken by Greg Robinson just before the mass suicide in Jonestown, which inspire the long essay by Brad Feuerhelm on photography as a field of mental investigation, when we know what happened just after those shots, when we already know the tragic finale.